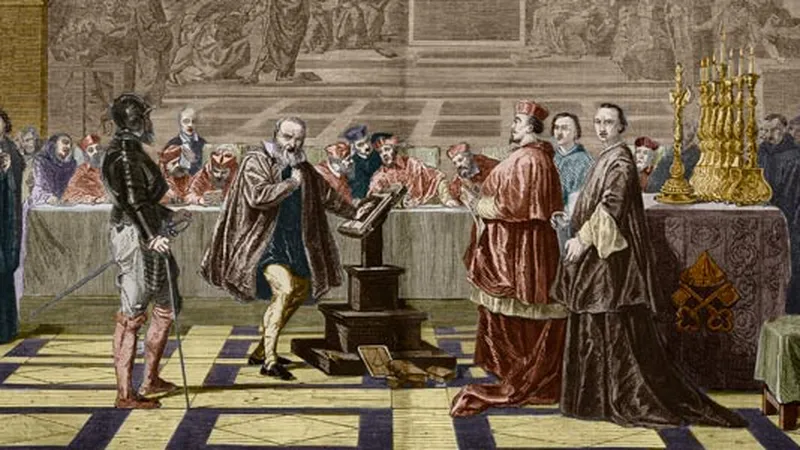

This post follows the posts on Galileo’s trial background and what happened at the re-enactment. Time to give my verdict. The most common “populist” argument is that the Galileo verdict was a travesty that represented a clear case of religion repressing science despite “obvious” facts. The alternative is often a defence that the Church was correctly cautious about the scientific status of Copernicanism, its social consequences etc.

On the science vs religion bit, it’s pretty clear: it can’t be a simple war if the vast majority of astronomers in Galileo’s day agreed with the Church’s position. In this respect, the Church was simply upholding the scientific consensus, just as modern governments talk about global warming being a problem based on the consensus1. From a certain perspective, Galileo was seen as a crank like the modern global warming denialists. Of course he had the luxury of being right. [EDIT: Or at least have a theory that, with the benefit of hindsight, is closer to the right direction.] But to blame the Church for not being psychic doesn’t seem fair to me.

Of course, the counter-response is that it was still wrong to make Galileo’s dissent a crime. In other words, Galileo might be guilty based on the laws at the time2 but the laws themselves were terribly unjust. And it’s hard to find anyone these days who disagrees. As I mentioned in a comment to my guest post on Faith Heuristic, one of the great changes we’ve seen since the Enlightenment is that almost everyone believes in the freedom of conscience and that heresy (ie. thoughtcrime) should not be punishable by law — even the staunchest of religious conservatives3!

So of course I judge the Church’s actions as wrong. (Even though this is projecting back modern morality, it’s still appropriate in many cases including this one.) But then, I don’t see Galileo as being particularly special. If the Church owes Galileo an apology for convicting him on thoughtcrime (as they surely do), it is no more of an apology that the one owed to all those convicted of heresy. Galileo is then special just because he happened to be involved in the most famous case. But to me that’s a bit arbitrary.

The natural retort is that this trial showed the reason that thoughtcrime legislation is harmful. Before the trial, Galileo was involved in a scientific debate with his peers about the Copernican theory. After the trial, Catholic astronomy took a sharp downturn as natural philosophers turned to less controversial topics. If the trial never happened, Galileo would still have been a minority. But if he was out in the trenches for the rest of his life (and not under house arrest), Copernicanism might have been taken up sooner. Which is important because, despite the many problems with Copernican theory, the earth does go round the sun. So you might say that when you forbid certain kinds of speech, your society stagnates in terms of science/arts/academia. Again this is true. But even if the Galileo trial never happened, even if all the thousands the Church convicted of heresy over the years had no heresies that would be useful, would that make the idea of punishing someone for thoughtcrime any less abhorrent?

Ultimately, the church got trapped by its own dogma. In 1616, Cardinal Bellarmine admitted to Galileo that if he could prove that the earth goes around the sun, the Church would then have to reinterpret the Biblical verses metaphorically (thereby going against the Church fathers). So from a certain perspective the Church was even admitting that Copernicanism could be true. And if it were true, it would cause Catholicism great embarrassment to cling to the literal interpratation. This is what Galileo’s theological argument was, and this is exactly what happened. But with Copernicanism branded heretical, the Church shut its own door to potential investigations of something that it admitted could be true, something that if it were true should be investigated ASAP to prevent a PR blow to the Church.

So of course the trial was immoral as all heresy trials were. But it was also problematic even from the perspective of the crusty old theologians. Large religious bureacracies are often more about politics than sticking to pure ideas like “heresy”. If the Pope didn’t feel personally insulted by Galileo, if conflicts with Protestants didn’t result in the authoritarian dick-waving4 of “my dogma’s bigger than yours” and if Galileo didn’t try to make theological arguments thereby encroaching on the turf of another profession, things would probably have been different. Alas.

Notes

- The operative word being talk

- Galileo was not to argue for Copernicanism as a true theory but only as a mathematical tool. But to any reader of the Dialogue, this is not what Galileo does — he is quite clearly advocating the truth of the earth going around the sun.

- Of course there are hold-outs to even this idea but as far as I know they really are few in industrialised countries that have had a long tradition of free press etc.

- Expression totally stolen

0 Comments