Tonight, the University of NSW is hosting a re-trial of Galileo, organised by my honours supervisor Peter Slezak. I was lucky enough to to retry Galileo in my undergrad degree (when Slezak taught a couse on it) as a prosecutor*, so it’s great to see that this has been taken to a higher footing with ABC TV filming and many notables playing parts in the trial (including the dishonourable Bob Carr a the Duke of Tuscany).

I’ll post on the retrial tomorrow or Wed. Today I thought I’d give a quick retelling of the historical events. Here’s a previous post that talks about how the earth revolving around the sun wasn’t at all scientifically obvious at the time of the trial. Now, to the narrative itself (which should dispel some myths):

Copernicus’s Theory

- Around the time of Copernicus, the theory of heavenly motion is the Ptolemaic theory which has the earth at the centre. All astronomical theories are considered only as mathematical devices used for calculating positions of planets; not as theories about reality.

- Ptolemaic theory employs a device called an equant. An equant is a point about which a planet moves with the same [angular] speed. This point is NOT at the centre of the system, in fact, each planet had its own “centre” of motion, all away from the earth which was considered to be the geometric centre.

- This lack of nicety bothers Copernicus so he creates a system with the sun in the centre. The system has no equants. The system isn’t simpler overall because it still used the other old mathematical tricks (such as epicycles).

- It seems Copernicus believes his system to represent actual reality. But because almost everyone else considers astronomical systems to be mathematical devices only, after his death people tend to use his system for calculations only. They didn’t think the earth “really” goes around the sun.

- Also there isn’t much observational evidence that might suggest the Aristotelian conception of the universe with the earth at the centre (on which the Ptolemaic is based) isn’t kosher.

Galileo & the Telescope

- The telescope is invented. It’s used for terrestrial observation — people probably spy on their neighbours with it before they ever use it in astronomy.

- Galileo hears about the telescope and constructs one based just on hearing about the idea. He points it at the heavens. He sees the following things:

- The moon is very jagged with craters and features much like the earth. (Aristotelianism held the heavens to be perfect so the lowly earth couldn’t be a planet.)

- Jupiter has 4 satellites. (This was the first example of a planet going around something whilst other things go around it, a good analogy for the earth in the Copernican theory.)

- Venus has phases just as the moon does. (This suggests it goes around the sun and not the earth as Aristotelianism would have it.)

- He publishes some of these in a pamphlet called Sidereal Messenger. He considers these observations to lend support to Copernicanism but does not mention this in the pamphlet.

- The major scientific objection is that Aristotelianism has no concept of inertia. So they thought if the earth spins, a cannonball dropped from a tower would go straight down while the earth continued to spin, thereby ending up hundreds of metres away from the tower’s base.

Galileo’s Biblical Problems (1615-16)

- The major theological objection is that some verses in the Bible imply the sun goes around the earth. Especially a passage in Joshua where God stops the sun to extend the day so the Israelites can slaughter more Amorites. Church tradition interprets this verse literally so to undermine it would undermine the authority of the Catholic Church to interpret the Bible.

- Galileo’s opinion (as a good Catholic) is that the Bible is not meant as a science book so scientific matters should not be a point of doctrine that faithful must believe. If the best science of the day contradicts a literal reading, we are free to reinterpret the passage metaphorically even though prior Church Fathers did not.

- This is the position of the Catholic Church today. But in Galileo’s time, it is not. Trouble ensues.

- Galileo makes his theological opinions known amongst some high circles and some clergy get offended that an layman is dictating “amateurish” theology to them. They complain to the Roman Inquisition (which is NOT the Spanish Inquisition but a much less bloodthirsty Inquisition).

- The Inquisition temporarily bans Copernicus’s book and Galileo is personally warned not to hold or defend Copernicanism. He agrees.

The Dialogue and Fallout (1632-33)

- Years later, the Pope dies and Cardinal Barberini gets elected Pope. He’s an old friend of Galileo’s — in fact before he was Pope, he wrote a little “love poem” praising Galileo. Platonically speaking, of course…

- Things are looking up for the theory so in 1632 Galileo arranges to write a dialogue that discusses the merits of the Ptolemaic and Copernican theories. Hypothetically of course, since the Church proclaimed that Copernicanism was heretical to hold as a description of truth (holding it to be a useful mathematical instrument was ok).

- Galileo writes a brilliant scientific classic (The Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems). Unfortunately for him, the book is very clearly an endorsement of Copernicanism. The mouthpiece of Aristotelianism is called Simplicio (a famous Aristotelian philosopher, but the point is lost on most people) who’s a blubbering idiot.

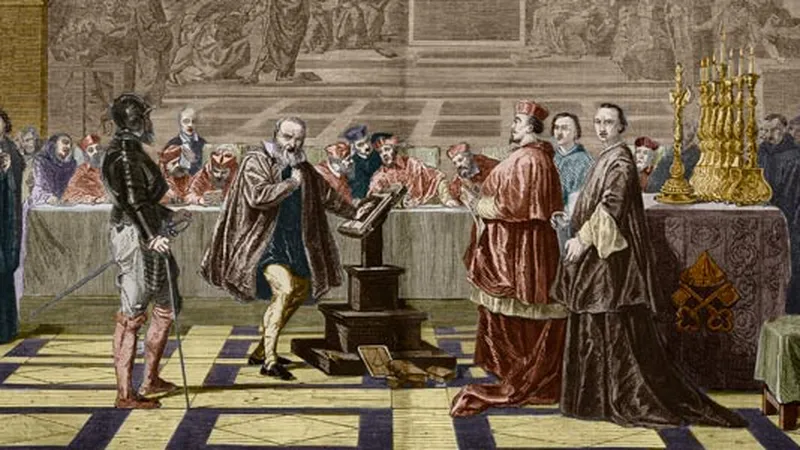

- There’s an uproar and by 1633 Galileo is called to appear before the Inquisition. He is deposed and maintains the book was strictly hypothetical etc.

The Trial

- The prosecution produces a document from 1616 warning Galileo to never even discuss the theory. Then Galileo produces the document given to him by the Inquisition in 1616, the one saying he can’t “hold” the position but doesn’t mention anything about not even discussing them.**

- This contradicts the prosecution’s document so they’re slightly embarrassed. Galileo’s allowed to plead the case out, being found guilty of Vehement Suspicion of Heresy. This charge is medium on the level of heresy charges, the main [more serious] heresy charge is dropped. [EDIT: Made a mistake here, he was found guilty of all charges, but the point below is still true]

- Galileo takes a few days to come up with a graceful way to recant (as part of the “plea bargain”). His way out goes something like this: Last night, I reread parts of my own book just to make sure I wasn’t arguing for Copernicanism. Lo and behold, turns out on second reading I did write it in a biased manner, although it didn’t occur to me at the time. I guess I was just trying to be too clever in trying come up with arguments for Copernicanism.

- Galileo spends the rest of his life under house arrest. He goes on to write Two New Sciences where he continues his physics experiments. Some of this contributes to a new understanding of motion that shows people Copernicanism could work, which starts the slow process of converting mainstream scientists to Copernicanism (with Galileo as the mouthpiece). The process takes many decades and I think it’s really only Newton who removes the doubt from the last hold-outs.

Now let’s see what arguments are made tonight in a public forum!

*We won, because Galileo was guilty. More on that later.

**Some think this means Galileo was framed by his enemies who forged a document. But according to a lecture given by Professor Finocchiaro at UNSW last Thu (in preparation for the trial), modern consensus is that this document WAS drafted in 1515 by error and never given to Galileo but kept in the archives.

0 Comments