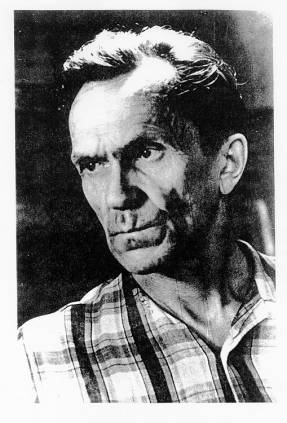

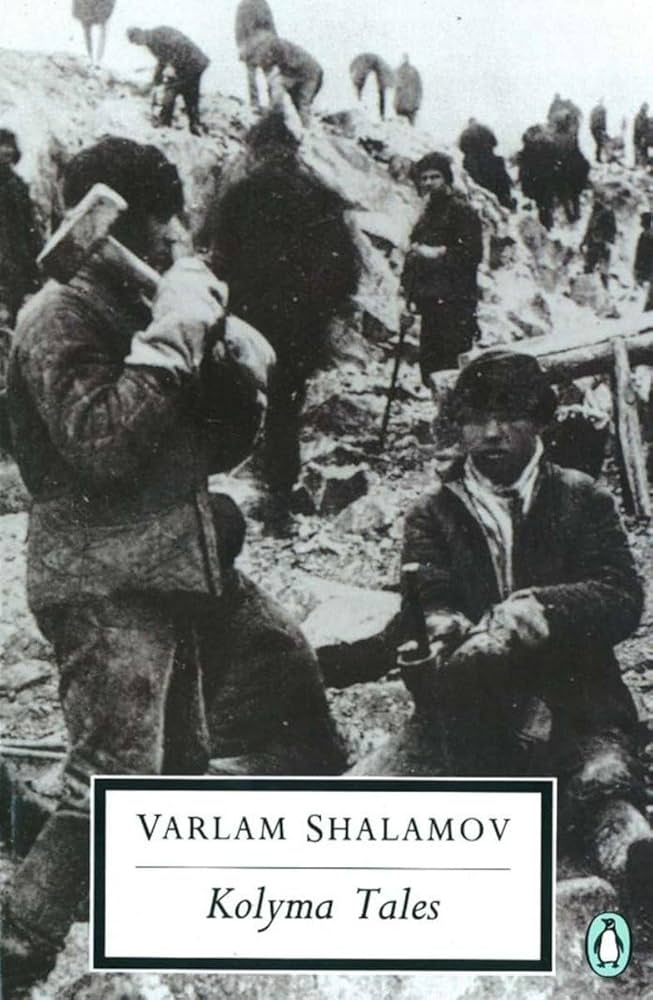

I’ve been reading a lot about the Gulags lately including the monumental Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. I’ll post more later but I thought it was especially important to translate a page by Shalamov that I found. Varlam Shalamov is famous for his Kolyma Tales — a series of short stories that combines fiction and non-fiction to portray the horrors of the camps he was in.

I’ve been reading a lot about the Gulags lately including the monumental Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. I’ll post more later but I thought it was especially important to translate a page by Shalamov that I found. Varlam Shalamov is famous for his Kolyma Tales — a series of short stories that combines fiction and non-fiction to portray the horrors of the camps he was in.

The list below is a separate work and is a particularly poignant and terse summary of his long-term view of his experiences. The original is here. After I translated this by hand I found that the same site had another English translation here. Doh! I guess there’s room for an amateur’s translation to compete with a more official one. Mine has a few explanatory notes (the accuracy of which I don’t vouch for at all!).

What I’ve Seen and Understood in the Camps

- The extraordinary fragility of human culture and civilisation. A person becomes a beast after just 3 weeks — given hard labour, cold, hunger and beatings.

- The main tool for decomposing a soul — bitter cold. In Central Asian camps, probably people could hold it together for longer — it was warmer.

- I understood that friendship and camaraderie can never begin in difficult (properly difficult, where life is at stake) circumstances. Friendship begins in circumstances that are difficult but bearable (in a hospital not a mine).

- I understood that rage is the last emotion that remains in man. Enough flesh remains on a starving man just for rage — he’s indifferent to everything else.

- I understood the difference between prison, which strengthens the character, and camps, which decompose the soul.

- I understood that Stalin’s “victories” [aNadder: in WWII? Or in internal politics?] happened because he killed innocent people. An organised group (even ten times less numerous but organised) would have swept Stalin away in two days.

- I understood that man became man through being physically tougher and more tenacious than any animal — no horse can bear the conditions of the Far North.

- I saw that the only group of people that remained at least somewhat human amidst the hunger and abuses were the religionists — almost all the sectarians and the majority of orthodox priests.

- The first people to lose it are Party workers and military men.

- I saw what a formidable form of argument a simple slap in the face presents to a member of the intelligentsia.

- That the people tell who are in charge by the strength and intensity of the beatings they give.

- Beatings as a form of argument are almost unanswerable (method #3 [aNadder: not sure what that last bit is]).

- I found out about preparing conspiracies [aNadder: ie. fake charges] from the masters of said craft.

- I understood why in jail, you find out political news (arests etc) quicker than outside jail.

- I found out that the jailhouse (and camp), a “bed-pan” is never a “bed-pan”.

- I understood that you can always live by rage.

- I understood that you can always live by indifference.

- I understood why man doesn’t live by hope — there is no hope, or by will — what talk is there of will?, but by the instinct of self-preservation — the same feature that’s possessed by a tree, a stone, an animal.

- I’m proud that I decided in 1937, in the very beginning, that I will never be a camp work squad leader if my will might lead to another man’s death — if my will must serve the administrators thereby opressing other people — prisoners like me.

- And my physical and spiritual strength was greater than I thought during this great trial, and I am proud that I didn’t sell anyone out, didn’t send anyone to his death, or to a new camp term, didn’t dob anyone in.

- I’m proud that I didn’t write any requests until 1955. [aNadder: when they started “rehabilitating” millions of falsely-convicted inmates, whether they were freed already or posthumously.]

- I saw on the spot the so-called “Beria’s amnesty” — there was much to see there. [aNadder: This was the 1953 amnesty prepared by the Minister of Internal Affairs and Stalin’s right hand man Beria just a few weeks after Stalin’s death — he saw the writing on the wall. It released everyone whose sentence was 5 years or less, or about 20% of the 2.5M people in the camps at the time. As well as foreigners, children, pregnant women, elderly and people with a disability.]

- I saw that women are better, more selfless than men — in Kolyma there were no cases of men coming to their wives. While lots of wives came to their husbands. (Lists some examples). [aNadder: The Kolyma camps were so strict that at the end of your term you remained in perpetual exile in Kolyma, essentially living just outside the labour camp — and often doing the same jobs but as a “free” man/woman! Until the whole thing started dissolving around 1956.]

- I saw amazing northern families (consisting of free hired labourers and former inmates) with letters to “lawful husbands, wives etc”. [aNadder: not sure on this, perhaps this refers to the fact that many spouses of former inmates completely repudiated them and considered themselves married only in the legal sense?]

- I saw the first “Rockefellers”, underground millionaires, and heard their confessions.

- I saw those condemned to the harshest labour camp regime including the “D”, “B” contingent etc.

- I understood that you can achieve a lot — a hospital stay, a transfer — but only through risking your life — beatings, the ice of the penalty cellar isolator.

- I saw an icy penalty cellar isolater hacked out in the rock, and spent a night there myself.

- The thirst for power and unrestricted murder is great — from the Big Kahunas to regular guards — all with rifles. (Gives some references)

- The untamable propensity of a Russian man to complain, to dob people in.

- I understood that the world shouldn’t be divided into good and bad people but into cowards and non-cowards. 95% of cowards are capable of any treachery (incredible treachery) at the slightest threat.

- I am convinced that the labour camp experience — all of it — is a negative school, that you can’t spend even a single hour in it without it being an hour of corruption. Nobody had ever gotten anything good or useful from the camps at any point — nor could they. The camp is corrupting for all — both inmates and free hired labourers.

- Every county had its own camps, every construction project. Millions, tens of millions of inmates.

- Repressions did not just touch the top but all parts of society — in every village, in every factory, in every family there were family members of friends who were repressed. [aNadder: repression being the official term for punishment by the state, usually meaning arrest, conviction, labour camps and death.]

- I consider the months spent in the Butyr prison the best period of my life — there I was able to strengthen the spirit of the weak and there everyone spoke freely.

- I learned to “plan” my life only one day ahead — no more.

- I understood that thieves aren’t people. [aNadder: thieves meaning the class of Russian career criminals and organised gangs, for more details see two old posts of mine]

- That in the camps there are no criminals at all, but people who were near you (and will remain near you tomorrow), that were caught beyond the line but didn’t themselves cross the line of the law.

- I understood what a terrible thing is a young boy’s pride — it’s better to steal than to ask. Boasting and this pride lead youth inmates to the abyss.

- Women have not played a major role in my life — the camps were the cause of this.

- That to know people is useless — since I cannot change my attitude towards any scoundrel anyway.

- The last in the marching lines are hated by all — by the guards and by their inmate comrades — the straggling, sick, weak, those that can’t run in the cold.

- I understood the meaning of power, the meaning of a man with a rifle.

- That the scales [aNadder: by which you measure life?] are shifted, and this is a chief feature of the camps.

- That to change your state from an inmate to a free man is very difficult, almost impossible without long acclimatisation.

- That the writer must be a foreigner with respect to the issues he is describing — if he knows the material intimately, he will write it in a way that nobody else would understand.

0 Comments