I’ve recently realised that not everyone is aware of this wonderful sentence. Having unrestricted access to a blog, I might as well introduce it. But first, a bit about garden path sentences. These are a lot of fun. They’re sentences which while grammatical have something about them that make most people’s brains stumble when you read them. You then start to fumble for a reinterpretation of the sentence. Hopefully you get the interpretation but even if you do, it takes some concentration to apply it when looking back at the sentence. Here’s a short selection of some good ones (some are from here):

I’ve recently realised that not everyone is aware of this wonderful sentence. Having unrestricted access to a blog, I might as well introduce it. But first, a bit about garden path sentences. These are a lot of fun. They’re sentences which while grammatical have something about them that make most people’s brains stumble when you read them. You then start to fumble for a reinterpretation of the sentence. Hopefully you get the interpretation but even if you do, it takes some concentration to apply it when looking back at the sentence. Here’s a short selection of some good ones (some are from here):

- The man who hunts ducks out on weekends

- The old man the boat

- The horse raced past the barn fell

- The man who whistles tunes pianos

- The prime number few

- Mary gave the child the dog bit a bandaid

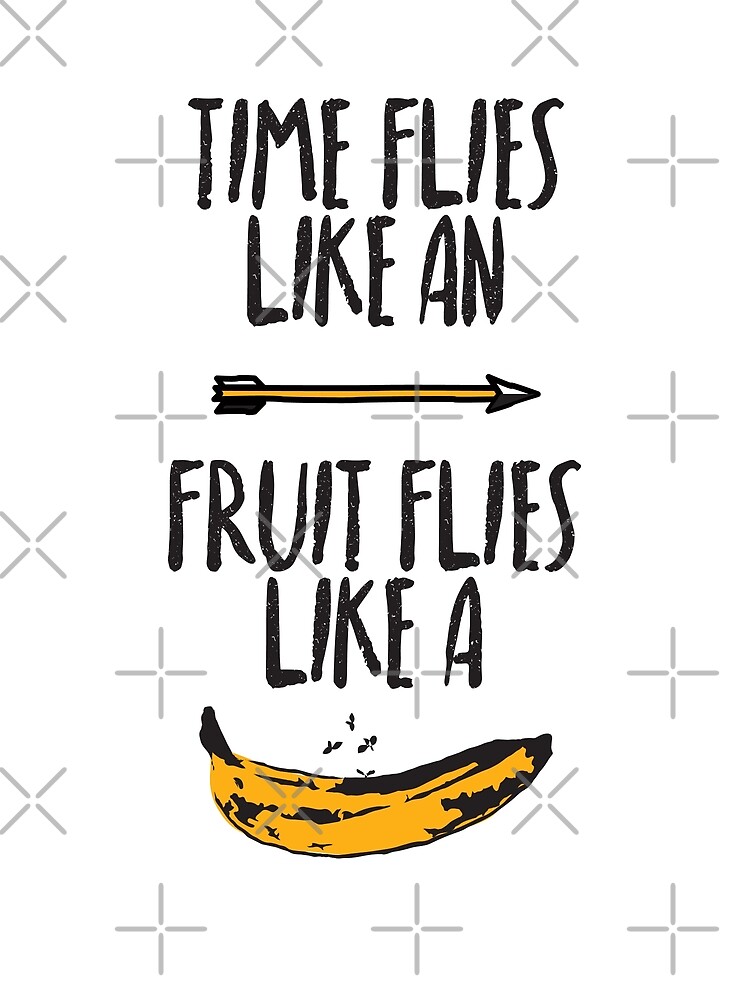

- And of course ‘time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana’.

The first thing you might notice is that (except the last one) the syntax, while grammatical, is a bit unusual. Most of these fall into 2 categories. The first is the use of relative clauses while omitting optional words like “that”. Consider: “the horse [that was] raced past the barn fell” and “Mary gave the child [that] the dog bit a bandaid”. The second category is where a word functions as several types of speech. For instance, in the first example the misunderstanding relies on assuming that “ducks” is a noun when it’s really a verb.

To cut a long story short, garden path sentences illustrate a few elements of the [largely Chomskean] syntax program in modern linguistics. Almost all sentences/utterances are ambiguous in terms of syntax, scope etc. Because of this, a person cannot consider all interpretations that fit a sentence when they’re listening to it in real time. Your brain parses the sentence using inference to the best explanation — for instance using the prior knowledge of “ducks” as being something typically hunted to interpret that word appropriately. It is this syntactic tree that’s thrown into disarray with garden path sentences.

This also shows how hard it is to get a computer to understand or even parse human text. The number of correct syntactic trees that a sentence can be fitted under is immense, probably growing exponentially as the sentence increases. To parse in the same way as the native “human” intuition, a program must have access to a lot of background knowledge about the human world. Only then will it use a different tree for “time flies like an arrow” and “fruit flies like a banana”.

Just for interest, here are just some of the possible interpretations a program might have for the first sentence:

- The intuitive interpretation you gave yourself

- The species of fly called time flies are fond of arrows (this is the interpretation that’s the “standard” one for “fruit flies like a banana”)

- Use your stopwatch (in the same way as an arrow would) to time the movement of flies

- Use your stopwatch to time the movement of those flies that are like an arrow

- If we don’t know that it’s a complete sentence, it could be a noun phrase referring to those species of time flies that are arrow-shaped. If you have trouble with this, consider the square-bracketed noun phrase in this segment I just made up. “The swarm of flies actually aligned themselves in the formation that was shaped like an arrow! A second swarm of flies made a circle but I think [flies like an arrow] are prettier.”

- *Hey time, I want you to know that flies enjoy arrows!

- *Hey species of fly called time flies, you should enjoy an arrow!

The last ones that I’ve asterisked would be true for a computer interpreting spoken input because then in addition to the words it must consider the possible punctuation between words that is not provided directly.

Bottom line is that everything we speak is highly ambiguous. Just like many other brain functions, understanding language seems to be a process that integrates many other processes at various levels. We don’t “just” take into account small fragments and put them together, but even our basic understanding of language is affected by the pragmatics (ie. context) and our real-world knowledge. Which means machine processing of natural language is a tough nut to crack indeed, no matter what theory of language you espouse.

0 Comments