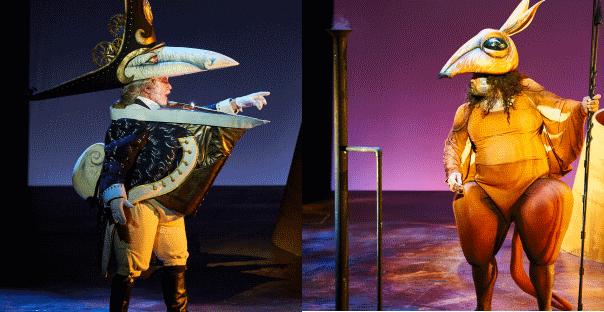

Earlier this year my partner got us tickets to the opera production of The Rabbits because a lot of people recommended it to her. Now, I live in a massive ivory tower when it comes to children’s literature. Before that I’ve never heard of John Marsden and Shaun Tan’s acclaimed book from the 1990s. My only context was that it was an allegorical opera about colonialism that featured rabbits. The place was packed, being part of the Sydney Festival. At least half in the audience were children, which makes sense given that it described itself as an opera for “children and families”. I wondered how the production would deal with the incredibly challenging task of talking to a younger audience about Australia’s racist past and present.

The message was disappointing to say the least.

It felt like the opera was intended for a “general audience” which in 2016 Australia unfortunately means non-Indigenous. On the positive side then, the play exposes non-Indigenous children (from a certain socioeconomic background) to at least some aspects of Australian colonialism. I don’t know much about how well this is taught in schools but I imagine not very. Anyway, of ALLLL the current mainstream productions about Australian colonialism this was the most on-point.

Here are some of the things I found myself cringing about (spoilers):

- Although there’s a fairly diverse cast, the main role is played by Kate Miller-Heidke. I didn’t find her role obvious but she seemed to be some kind of narrator and Dreamtime spirit all in one. Now of course she is there because of Reasons (eg. she was the one commissioned to write the music). Still, this turns it into a story about the horrors of British colonialism in Australia, presented to a disproportionately white audience through a white conduit/guide/authoritative voice. Is this to make us more comfortable? Does this follow the trope of stories needing a white narrator through which “we” can frame the stories, make them “objectively relatable” to ourselves? So that we’d believe her?

- Given the actual history+legacy of colonialism and racism outside of a fictionalised work, it’s a bit dodgy to use animals as stand-ins for people. Yes, the “British” here are also animals but I reckon the literal dehumanisation of people to tell THIS story should have made the authors uncomfortable and didn’t. Especially given that the Numbats that are a stand-in for Indigenous Australians have at least a couple of things in common with standard racist caricatures.

- The story uses two different species of animals, which I think is pretty racist. At the very least, it sneaks in a biological essentialism that would be considered pretty extreme these days if it wasn’t couched in allegory. You might say, give them a bit of slack, how else could this have been presented in a way that children would understand? I’m not a children’s author so that’s not my area of expertise. But I’m pretty sure there are alternatives. You can definitely make the same animals into two groups that look different from each other. Interestingly, based on the opera’s name I assumed that they would all be rabbits. TBH, I’m not sure I’d have gone if I knew it would segregate the races like that.

- The opera presents the stolen generation, but instead of child actors, the live action Numbats carry plastic toy Numbats. It’s these toys that get taken away. Yes the opera is trying to be a bit surrealistic and bewildering, which might explain why this decision was taken. Still, it’s literally dehumanising to make these plastic animal dolls as stand-ins for real children. I didn’t expect the trope of “people of colour used as props in a work” to come to life so literally either. Because they’re plastic toys this means they can’t tell us their own story of what happened. It means that they can’t be anything but passive: first they get carried around by their parents (like property), then they get taken away (without resisting) and stay away not doing anything.

- On the aesthetic side, it’s easy for allegories to get too close to the subject matter and stop being allegories. In The Rabbits, the stand-ins for Indigenous Australians, the British Empire etc were so close I don’t see why they weren’t just referenced even more directly. It was definitely good that the message didn’t get watered down into a wishy-washy “universal” colonialism-is-bad message and that it spoke to the specific details of Australia. And maybe making it an allegory does make it a bit easier for children to understand — even if it’s the thinnest allegory I’ve seen. Still, it just says a lot about the desensitisation of white Australia to reality that there’s a perceived need to put animal costumes on people to get the audience to be receptive.

- The British are portrayed very negatively, to the point where they become the Other. We’re can’t think of them as anything but abominable characters that are Not Us. This feeds into the falsehood that racism is about individual personalities who “are” racist. As opposed to the systemic racism of institutions which we might all be involved in, in different ways (especially if we’re white). I wonder if the takeaway a white audience will get is “these British are so horrible, I’m glad I’m/we’re not like them! Come on kids, let’s go home.”

- The British are rabbits and they spread very quickly in Australia. I know that racist science was never deployed against British settlers. Still, I hoped the intimate role racist eugenics have played in the history of colonialism throughout the last few centuries would at least given some pause to labelling the antagonists of your story as “breeding like rabbits”. This is similar to the whole issue of using animals at all.

- The British have their different occupations which can be inferred from their costumes, actions etc. But the Indigenous Australians pretty undifferentiated. They don’t really have easily identifiable roles, personality traits, occupations etc. They’re just “the Indigenous population, I mean Numbats”. Again, a little dehumanising.

- Because the two groups are portrayed as very clearly bad vs good, this means that the Indigenous population gets stuck with a slight vibe of the noble savage. I guess in an allegory like that it’s very hard not to make archetypes instead of characters. But then we don’t get the same kind of characterisation of people’s inner lives.

- After the failed uprising, the Numbats are depicted as passive. Their children are taken away and they pine and grieve for them. They are portrayed as largely victims with no contemporary agency. This obliterates all of the achievements, activism and action from Indigenous Australians from over the last century. The opera ends with a modern-day landscape where they are still [only] victims from the actions of invasion, genocide and the stolen generation.

- A very minor thing but at the start of the play, the first Europeans that come to Australia are scientists who seek to do something like “impose their narrow imperialist notion of objective truth on the spirit of the landscape” or some such. There is a very important history of scientific racism to be told, as well as the role science played in colonialism (although it might be impossible to tell it in an opera aimed at children). The inaccurate dig they’ve chosen is a cheap shot and seems to paint science itself as a western imperialist enterprise. Which is dismissive of science that took place in non-Western contexte, of contemporary science that is done by people of colour (as if it’s not “their” thing?) and, I guess, racist.

Throughout the opera I wondered if my guess that the writer wasn’t Indigenous was correct — I forgot that it was by John Marsden and Shaun Tan who are not. Interestingly Shaun Tan’s website describes the original book as not being primarily for children meaning that counter-objections to some of the above to the tune of “but it would be impossible to be nuanced in a children’s story!” should hold less weight.

After I jotted down the above notes I found an interesting 2010 essay (about the book version) that I recommend for further reading: Who will save us from the rabbits?: rewriting the past allegorically. It mentions some of the points I had above but also focuses on the degree to which the original book implicitly acknowledges the terra nullius narrative, as well as portrays Indigenous Australians as people without agency who need ‘rescue’ (“who will save us from the Rabbits?”).

None of this is to say that the positives of The Rabbits (bringing these ideas to people who might not be exposed to them) might not outweigh the negatives. Maybe they do. But that’s probably not for any non-Indigenous person to say. Expertise matters.

What do you (esp if you’re Indigenous) think?

0 Comments