One genre that does well online is photo-essays about food around the world. The food is often fascinating but the pieces can also elicit some interesting and simplistic reactions from the online audience. The form I’ve seen this take is people from wealthy English-speaking countries looking at examples of food from “their” countries vs “other” countries and comparing it. Here are three photo-essays that I’ve seen reveal some simplistic attitudes on the part of the audience (I’m not sure how much we can attribute this to the photographers).

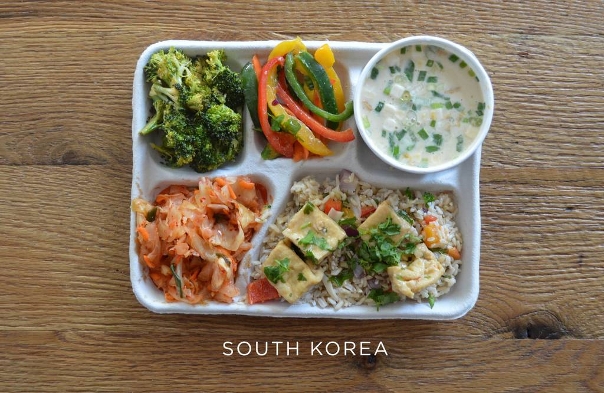

School lunches around the world

This was a blog investigation that got coverage in mainstream media. A selection:

The main subtext the audience is reading from this series (and the other two) are how crap the food in the English-speaking countries is, compared to much “better”, “healthier” or “tastier” food in other countries. And yes: based on this series of images, the US and UK have the junkiest school lunches.

I say “based on” to highlight that these photo-essays often an issues with accuracy and representativeness. On accuracy, the news story about this photo-essay had several commenters say they’re from one of the countries and the school lunches are nowhere as nice as the photo. Even without going to school in all those countries, you can tell it won’t be fully accurate because all meals are on the same tray and therefore are about the same size. How likely is it that the food in all those countries differs only in substance but not in quantity?

The problem of representativeness is that each photo is often read as “the” lunch from that country. Now, school lunches can be pretty standardised so this is more likely to be accurate than for the other two photo-essays which show food in the “real world”. But even then, think of how much variation there would be in, say, India’s school lunch program (maybe the greatest nutritional achievement in the history of humanity). Yet if this photo-essay included a tray from “India”, many readers would take that at face value.

There are also many cultural assumptions about which lunch we’re supposed to consider “tasty” or “attractive”. How many people look at the “foreign” meals as exotic and therefore considered more palatable? If you find the USA’s peas boring, South Korea’s plain broccoli is just as boring. But I bet more English-speaking readers would have been force-fed something like the USA lunch which affects how they react.

Some comments also noticed that a few of the lunches we’re supposed to be praising to are a bit high-carb and high-GI and so not objectively the “best” (eg. Ukraine, Finland). I think they’re not too bad but the point is that “Western rich countries = bad food, other countries = good food” is a terrible narrative. We’ll see this theme in the other photo-essays. Yes, the UK and USA lunches should be improved, but there’s a lot more to it than that.

A worldwide day’s worth of food

Here, individuals from around the world posed with all of their food for a day. Here are some of them. I’ve added the name of each person’s country, the original also had the food description and calorie count:

Namibia

Brazil

USA

Spain

Egypt

Iran

Again the main problem is representativeness: a food story about an individual becomes a stand-in for the whole country. This is reductive at best and racist at worst, especially there are lots of countries where all of the meals above might be eaten on the same day by different people. At least this photo-essay also describes each person’s occupation so we can take that into account in terms of variation.

These photo-essays often have images from “third world countries” (a reductive concept in itself) which can serve as poverty porn. The most obvious one is from Namibia and it does show how very unindustrialised living can be a lean existence. Something might also look lean but not be. The Brazil fisherman’s meal that day actually had the most calories out of anyone in the exhibition.

Then there’s the junk food shaming. For sure, many industrialised countries over-consume junk food – but this has a broader context. The US employee worked a long shift in a mall where not much else is available. US photos I didn’t include were a soldier (whose food is picked) and a man waiting for bariatric surgery (on a very healthy diet which suggests he was picked for fat-shaming purposes).

To overturn the simplistic dichotomy, the meals of the people from say Egypt and Iran had a lot more calories than the “Western diets” shown. That was my main reaction – these meals looked substantial compared to the US meal that I don’t think would fill me up. At least the context of occupation is apparent in this photo-essay: shepherds, bakers and cyclists do need a lot more calories.

Hungry Planet: what the world eats

This is the most famous example of the genre, a book that’s also an exhibition that depicts families from different countries and their groceries for the week (with the food cost). Here are some families.

USA

Canada

Australia

I guess these are meant to make us cringe but there’s a lot of context many readers would ignore. Most people would not attribute the choice of groceries in a refugee camp (image further down) to personal choice. And yet for “developed” countries a lot of people seem to entirely attribute the food to personal choice. As if food culture (and food deserts) didn’t exist. As if the fact that the Australian family probably being Indigenous and living in a rural area, is irrelevant or at best a minor force. No no, let’s just look at the pictures and gasp at how much junk people are choosing to consume in the “filthy rich” countries.

Japan

Japan again

This is one of the few cases of two different meal types being shown from the same country. You mean there’s no such thing as a “Japanese family’s groceries”? But this oddity actually highlights the extent to which the other families are stand-ins for their country. For the second family, you’d need to know about what’s in those packages (ie. modern Japanese food culture) to form a clear picture of what’s going on. Again this breaks the “veggies good processing bad” dichotomy that millions have read from these images.

Equador

Bhutan

India

The above images are typically the ones people praise as being healthy. It is great to have lots of veggies; but I think if you’d asked the first two families about how they feel about their groceries, they’d say they want more variety, more calorically-rich foods, more treats. These are also not countries known for the best health and nutritional outcomes so again there are more variables at stake. The Indian family has the groceries that personally most appeal to me, but they’re probably a well-off family in a country of hundreds of millions of families, many of which cannot eat healthy.

Chad

Mali

That was the obligatory poverty porn. The food rations for the family who fled Darfur and are in a Chad refugee camp are terrible. My guess about the biggest problem with such cuisine is not being full (which could happen when those grains cook) but it being a low-protein, low-micronutrient diet. But even when you get to the better groceries of the family from Mali I don’t think I’m that qualified to evaluate how good or bad this food is. And if you haven’t lived like that family, you’re probably not either.

Mexico

Germany

Italy

France

It’s not just English-speaking countries that have lots of junk food! One good point about the groceries of all these families is that there’s more fresh fruit and veg compared to the English-speaking families pictured.

China

Poland

Turkey

Greenland

Mongolia

Kuwait

These photos show that there’s genuine variety that’s about a lot more than income or the “corrupt influence of Westernisation”. The migration into cities and into more white collar jobs really can make the diet look less traditional and more Western as the most labour-intensive dishes may be toned down (the Chinese family). Some people don’t have many veggies for geographic reasons (the Mongolian family) while for others non-locally-sourced food is a must (the Greenland family). Some benefit from industrialisation without moving completely to Western ingredients (the Kuwaiti family).

Looking at what people around the world eat is fascinating. But to get something out of it, you have to abandon lazy stereotypes about income, race and class and look at the eating habits of each person as the product of both choice (except in refugee camps, prisons etc) and global forces. To consider externalities only for people in “poor countries” is patronising and smacks of the terrible first world problems meme.

Also if you live in a wealthy country you could probably do with eating more veggies.

0 Comments