There seems to be an interesting relationship between a key puzzle in metaethics and a key puzzle about consciousness.

There seems to be an interesting relationship between a key puzzle in metaethics and a key puzzle about consciousness.

In the field of metaethics, the main aim is generally to propose a theory of what it means for something to be moral, with justification. (It is the somewhat separate field of applied ethics that deals with applying particular metaethical theories to specific situations.) Some examples are ethical egoism (worry about yourself), the various forms of utilitarianism (crudely, maximising various forms of well-being), Kantian deontology (only act according to maxims that you would reasonably wish everyone else would adopt) and so on.

However, there is a simple question that can be asked of any moral theory: “but what makes that good?”. This bit of one-upmanship is one of the most frequently used arguments for people wanting to criticise a particular system of metaethics. For instance, many who are against utilitarianism will say “sure, this system seeks to maximise well-being but how can you prove that that in itself is the right thing to do?”.

I’ve posted before about why I think this is probably a red herring. But there are some uncanny parallels to consciousness.

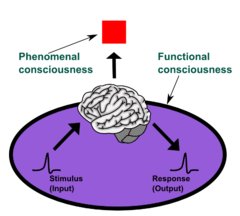

In the field of cognitive science and philosophy of mind, one of the main aims is to propose a theory of what it means for something to be conscious, with justification. Some examples are dualism (your soul is conscious), functionalism (crudely, consciousness comes from the functional arrangement of your neurons and can therefore be reproduced using any other medium) and so on.

In the field of cognitive science and philosophy of mind, one of the main aims is to propose a theory of what it means for something to be conscious, with justification. Some examples are dualism (your soul is conscious), functionalism (crudely, consciousness comes from the functional arrangement of your neurons and can therefore be reproduced using any other medium) and so on.

However, there is a simple question that can be asked of any consciousness theory: “but what makes that consciousness?”. This bit of one-upmanship is one of the most frequently used arguments for people wanting to criticise a particular system of consciousness. For instance, many who are against materialism will say “sure, an atom-for-atom replica of me will have the same behaviour as I do, but what reason do we have for believing they are conscious?”.

I’m not sure what the relationship between these two types of one-upmanship is but it seems to be very profound. Much more profound than the tricks themselves — in both cases I think these tricks are red herrings that are the source of most of the confusion in their respective fields.

Perhaps it testifies that our thoughts on what it means for something to be “good” or “conscious” is driven by some very deep intuitions. These probably exist as part of our cognitive heritage quite separately to rational thought. If so, then no matter how good a theory of metaethics or consciousness you might propose, our brains will always think that some essence is missing, that perhaps it’s not “really” consciousness or morality. Perhaps our intuitions about morality and consciousness are so Platonic that the fields themselves will be going in circles for decades to come (if current trends are anything to go by).

0 Comments