In the last few days, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (the living Boston marathon bomber) has been in the news again. Having been convicted on all counts in April, he has just now been sentenced to death by lethal injection. Coming off the recent executions of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran by Indonesia and the furore this has caused in Australia, this is a good time to examine the public’s reaction to the death penalty.

Firstly, about the process. Tsarnaev’s sentence was decided by a jury who could have also chosen not to apply the death penalty. However, apparently being anti-death penalty is meant to disqualify you from the jury. This has about as much chutzpah as requiring all US juries to be explicitly for the prison-industrial complex – because having someone against it would undermine the objectivity of the process. With Chan and Sukumaran, there was much made about President Widodo’s attitude to [not] granting a pardon. There is something very arbitrary about the death penalty pardon, decided by one person and this particular case highlighted it. Widodo apparently refused to review their case files and has been quoted misstating the crime they were accused of (source).

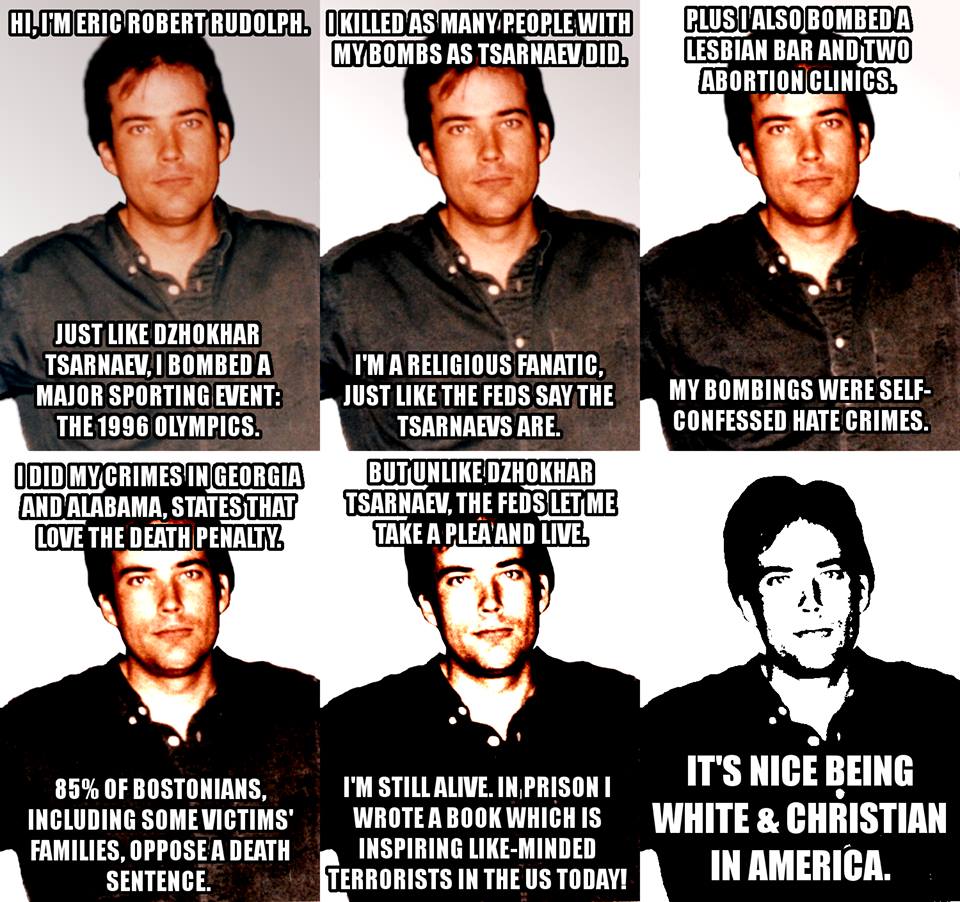

I won’t go over the racial disparities in the death penalty except to quote this graphic (HT Heina Dadabhoy):

If we zoom out, the death penalty is almost always a case of political posturing. Since death penalty cases are big, it would only be pursued for a fraction of the crimes which might qualify. How, oh how, shall we decide which cases to pursue? Why it’s gotta be something to do with our “values” (ie. “biases”) and cases which touch the “national sentiment” (ie. “which will help with my re-election”). As pointed out by this article, this is why both the Australian and Indonesian public are hypocritically against their own citizens being executed overseas but are for executions carried out on people who committed crimes against their populace. The only way for the death penalty to not be arbitrary is for it to be applied en masse so that it genuinely isn’t about “making an example” of someone. But we’re talking about proportions that go far beyond China’s and when it gets to the scale of mass murder there’s an implicit posturing there as well.

So, what about sympathy then? There was considerable outcry about the actual execution and while most people would not describe themselves as being sympathetic to Chan and Sukumaran, some of the rhetoric strongly implies sympathy. “Everyone deserves a second chance” is a bit of sympathy since I doubt most people saying this really mean “everyone”. There was an interesting undercurrent of Chan and Sukumaran being “one of us”, again highlighting the enormous gap between that and our sympathies for the thousands of Indonesians who have been extra-judicially executed by their state, esp in West Papua. And while Bostonians to their credit are overwhelmingly opposed to Tsarnaev’s execution, there’s been next to nothing in the Aussie media.

One of the rhetorical questions those who supported the executions of Chan and Sukumaran asked was “think of how many lives they would have destroyed with the drugs if they’d brought them into Australia?”. It’s actually possible, and worthwhile, to do the maths. Australia consumed about 2 metric tonnes of heroin in the 1990s. There are also approximately 1,400 deaths a year due to heroin overdoses. If 2 tonnes cause 1,400 deaths than the 8kg the Bali Nine were trying to bring in (or 0.4% of the annual supply) would cause 5.6 deaths from overdose, and presumably a lot of more havoc than just the 5.6 people.

Even though I’m strongly pro-legalisation, from a pure utilitarian perspective, this crime is actually of comparable magnitude to the Boston bombing. If not greater. Now, there may be greater diffusion of responsibility with the Bali Nine but I bet that’s not the reason for greater sympathy; I bet it’s just that the act of bombing a marathon is just so much more salient. Also if those stats made you take heroin smuggling more seriously, I invite you to crunch the numbers of companies that engage in pollution, CO2 emissions, deforestation etc.

The reality is we don’t do any kind of calculus when deciding whether to have sympathy for Tsarnaev or Chan+Sukumaran. It has to do with lots of arbitrary signals. There were lots of people believed in all sorts of conspiracy theories about the Boston bombimg because they couldn’t imagine that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev could be responsible, since he has such dreamy eyes. Generally we identify with people who we see as being like us, same as when we decide which fictional character is sympathetic or which disaster to donate money to.

Chan+Sukumaran lived in places we’re familiar with. Tsarnaev was born in Kyrgyzstan, a country most people can’t pronounce and know nothing at all about. In the aftermath of the Bali executions, a lot was made of the peaceful way Chan+Sukumaran met their fate including the Singing of Amazing Grace. This is a piece of cultural baggage that is familiar to most Australians and has pleasant associations. How much would the same Australians have identified with the defendants if the last thing they recited was the Shahada? Something Dzhokhar is likely to recite, thereby placing him out of bounds of the sympathy of many people. And of course everybody loves a great story of repentance, but what we consider as “turning your life around” is basically that which panders to our biases as well.

No matter how you slice it, the death penalty is arbitrary at every step of the way, from which crimes get prosecuted to who gets convicted to which cases get publicised in the media to which cases spark public sympathy and condemnation. The hypocrisy is also there at every level. It does no good to capitalise on the humanity of some of the victims of the death penalty because as we can see most of the time this is just done in a way to exclude others and make our sympathy for the victims conditional.

You don’t need to have sympathy for Dzhokhar, Chan and Sukumaran to unequivocally oppose their execusions as an arbitrary expression of a great injustice. I certainly don’t share those sympathies; I don’t really care if the victims’ last moments are occupied by Amazing Grace or the Shahada or Dennis Leary’s Asshole. The opposition to the death penalty should be much broader than that. It is about the justice system but also our own loss of humanity as our individual quirks and tastes allow us to oppose one execution but support another. As Laksmi Pamuntjak said in a great article (and this applies to all nationalities), Indonesians should be too familiar with death to support executions.

0 Comments