Every year, Edge.org asks the same question to about 100-150 scientists, philosophers, public intellectuals (and alas in a few cases, cranks) and publishes them. It makes the rounds on the interwebs every year and with good reason: often it’s fascinating reading.

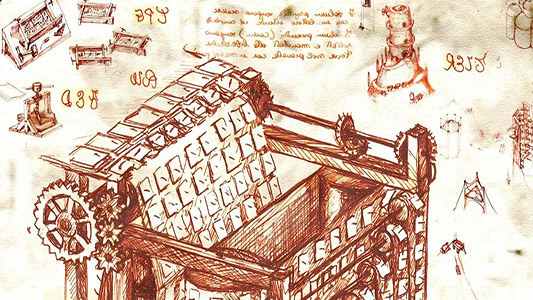

I’ve gone back to the archives to look at the whole thing since it started in the late 90s. One interesting question was from 1998: “What is the most important invention in the past 2000 years?” You can see the answers here.

My own answer from reading the question is toilets/sewage/sanitation/latrines and the germ theory they accompany. I’ve just finished reading a book about toilets (more posts on this coming up) that show just how important and neglected the problem is. I was a bit disappointed scrolling down and seeing nobody mention this until Carl Zimmer (who blogs at The Loom) hit the nail on the head:

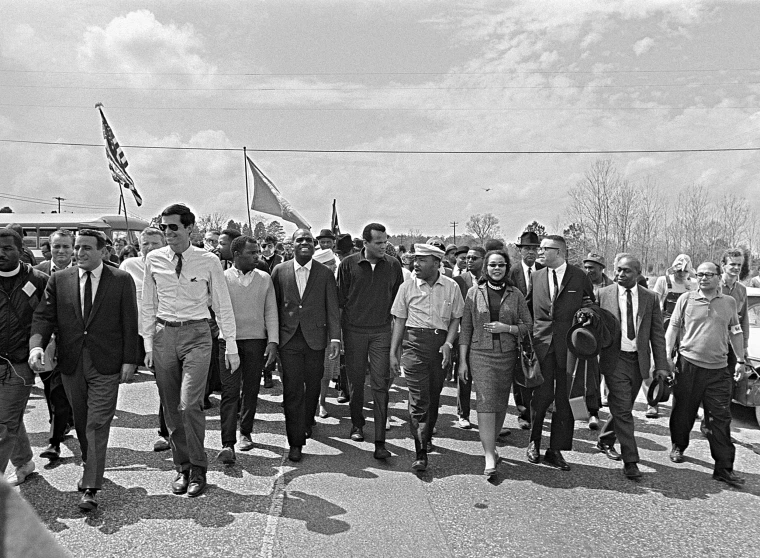

I nominate waterworks – the system of plumbing and sewers that gets clean water to us and dirty water away from us. I’m hard pressed to think of any other single invention that has stopped so much disease and death. It may not inspire quite the intellectual awe as something like a quantum computer, but the sheer heft of the benefits it brings about so simply makes it all the more impressive. John Snow didn’t need to sequence the Vibrio cholerae genome to stop people from dying in London in 1854 – he didn’t even know what V. cholerae was – but a pattern of deaths showed him that to stop a cholera outbreak all he needed to do was shut down a fouled well. Without waterworks, the crowded conditions of the modern world would be utterly insupportable – and you only have to go to a poor city without clean water to see this. Another sign of the importance of an invention is the havoc it can wreak, and waterworks score here again-by cutting down infant mortality they help fuel the population explosion, and they also let places like Las Vegas suck the surrounding land dry.

I’d even go so far as to put the importance of the invention of waterworks on an evolutionary scale with things such as language. For hundreds of millions of years, life on land has been crafting new ways to extract and hold onto water. With plumbing, however, you don’t go to the water – the water comes to you.

Hurray for Carl Zimmer! Other interesting and/or popular answers (excluding more obvious ones like the wheel or the printing press) were:

- the scientific method

- the pill

- the concept of zero

- double-entry bookkeeping

- calculus

- Christianity and/or monotheism

- the domestication of the horse, hay, stirrups (nominated by 3 different people)

Of course to an extent this is simply asking a person to reflect their own biases and interests. And as many on the list pointed out, the desire to be original might bias selections away from the cliches but one of the cliches (eg. the printing press) might well be the best answer. Still, all the responses make for a fascinating read. I’ll close off by giving Richard Dawkins’ full answer. As well as being brilliant, it (again) made me laugh at how ridiculous the accusations that those-described-as-New-Atheists are philistines or narrow-minded really are.

The telescope resolves light from very far away. The spectroscope analyses and diagnoses it. It is through spectroscopy that we know what the stars are made of. The spectroscope shows us that the universe is expanding and the galaxies receding; that time had a beginning, and when; that other stars are like the sun in having planets where life might evolve.

In 1835, Auguste Comte, the French philosopher and founder of sociology, said of the stars:

“We shall never be able to study, by any method, their chemical composition or their mineralogical structure . . . Our positive knowledge of stars is necessarily limited to their geometric and mechanical phenomena.”

Even as he wrote, the Fraunhofer lines had been discovered: those exquisitely fine barcodes precisely positioned across the spectrum; those telltale fingerprints of the elements. The spectroscopic barcodes enable us to do a chemical analysis of a distant star when, paradoxically (because it is so much closer), we cannot do the same for the moon – its light is all reflected sunlight and its barcodes those of the sun. The Hubble red shift, majestic signature of the expanding universe and the hot birth of time, is calibrated by the same Fraunhofer barcodes. Rhythmic recedings and approachings by stars, which betray the presence of planets, are detected by the spectroscope as oscillating red and blue shifts. The spectroscopic discovery that other stars have planets makes it much more likely that there is life elsewhere in the universe.

For me, the spectroscope has a poetic significance. Romantic poets saw the rainbow as a symbol of pure beauty, which could only be spoiled by scientific understanding. This thought famously prompted Keats in 1817 to toast “Newton’s health and confusion to mathematics”, and in 1820 inspired his well known lines:

“Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine –

Unweave a rainbow . . .”Humanity’s eyes have now been widened to see that the rainbow of visible light is only an infinitesimal slice of the full electromagnetic spectrum. Spectroscopy is unweaving the rainbow on a grand scale. If Keats had known what Newton’s unweaving would lead to – the expansion of our human vision, inspired by the expanding universe – he could not have drunk that toast.

0 Comments