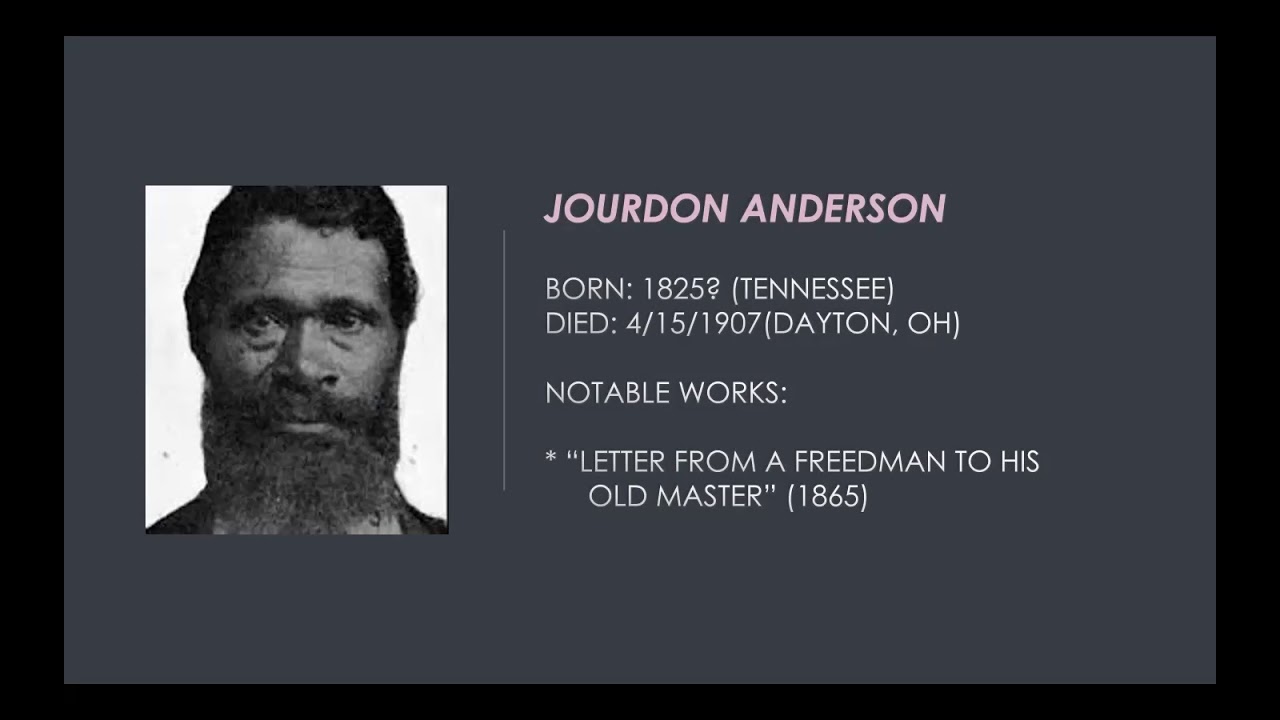

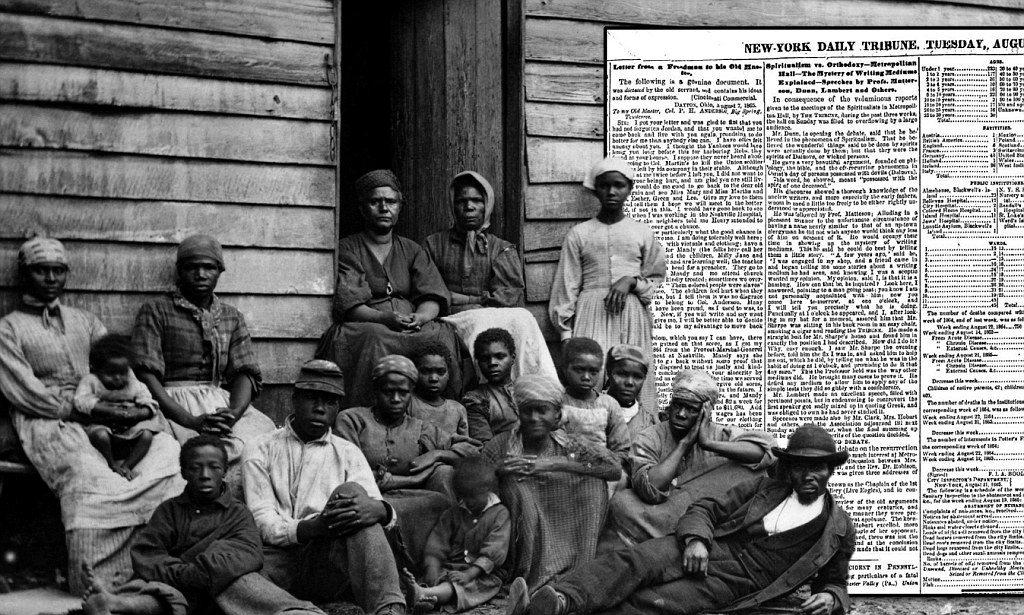

An awesome letter has been making the rounds on the internet. It’s a 1865 reply by Jourdan Anderson (a former slave) to his former master Colonel P.H. Anderson. P.H. Anderson wrote asking Jourdan Anderson* to come back to work for him. Jourdan Anderson was living in Ohio at the time, free and with a decent (in his opinion) job. Do read the whole thing, especially the punchline. I will quote a few choise morsels:

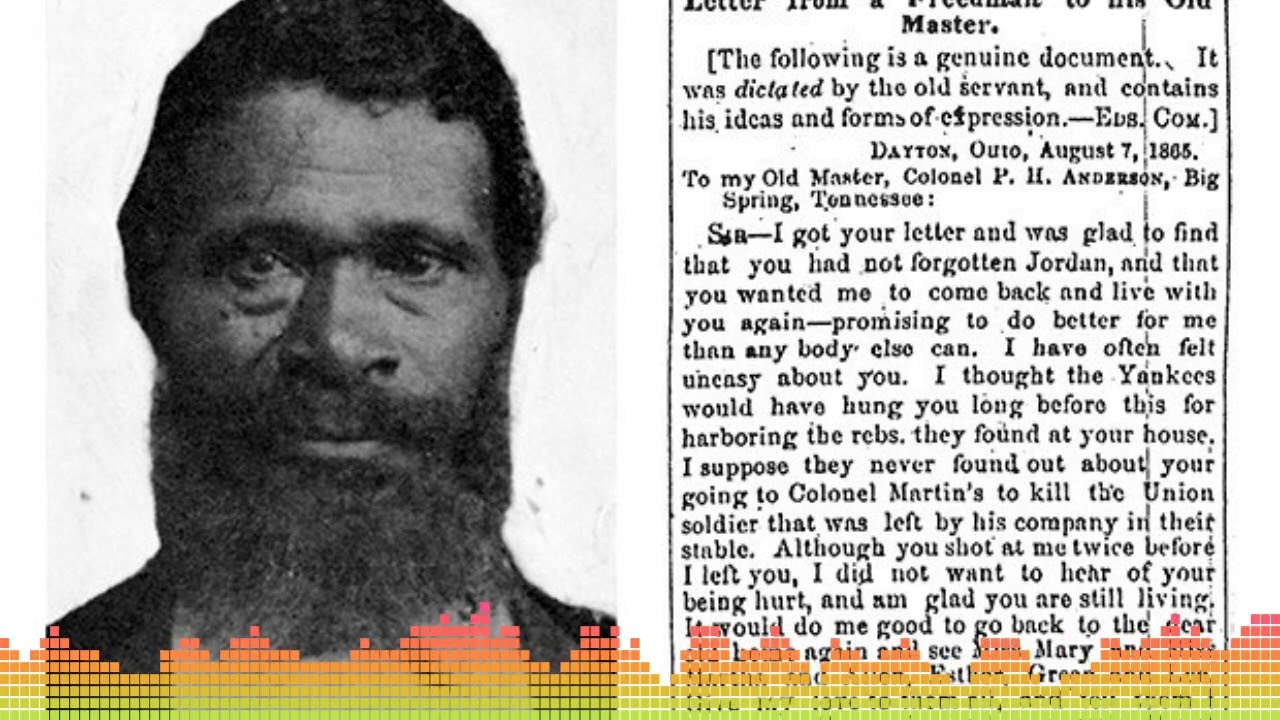

- “I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.”

- “I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing…Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.”

- “As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville.”

- “Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you…At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars…Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio.”

There are a few interesting issues the letter brings up. The first is authenticity. Sabio Lantz expresses skepticism, his skeptical mind asking “Wait, what if some Northerner made up the letter back in 1884 just to make his political points?” From my reading it means the letter might be perceived as too perfect and too eloquent to have been written by an illiterate Jourdan Anderson. The Huffpo’s post on the letter now has an update with quotes from a historian who has located Jourdan Anderson’s census record and the original letter published in a contemporary newspaper. So evidence for the letter being authentic appears pretty good but there is the suggestion of the letter being ghost-written by Jourdan Anderson’s children or his lawyer. An old thread on Snopes.com about this letter has some more info.

The problem with such doubts is that they rely on our assumptions of how eloquent an illiterate person might be, how large their vocabulary might be and so on. All of these we probably don’t have a huge baseline on. I bet you, dear reader, don’t personally know even one illiterate adult. I don’t. But that would be the first thing to think about or read about before we can evaluate how much ghostwriting there was. However from what I know about oral cultures, I think it might be a case of us underestimating illiterate people. Especially slaves, the vast majority of whom who were illiterate by force (as opposed to being a minority within a population expected to be literate). Personally I think the letter could well have been composed chiefly by Jourdan Anderson, although the final product is likely to have received some editing. Then again, my mum gets me to edit her emails if she’s writing something important and she’s got a master’s degree so that’s neither here nor there in terms of “detracting” anything from the letter.

But all of this is tangential to the main point of the letter. It is that P.H. Anderson actually wrote to Jourdan Anderson to ask him to come back. This part seems very well established indeed, even if you think the reply was ghost-written. Now, it seems strange that P.H. Anderson would have written in sarcasm or that it would be anything but a genuine request. Which seems very odd to us — how could he have seriously thought for a minute that the man who used to be his slave would volunteer to come back to serve him once again?

This comes back to the idea that we can’t help but project our moral views back onto history. When we think of the Nazis, a part of us has an image of men with moustaches marching around doing their Heil Hitlers and saying “ja, we’re so-o evil!” in German accents. Even if we know better. But from all we know in psychology, people almost never think what they’re doing is evil. In fact, they go to immense lengths to justify their actions, to others and especially to themselves. We find it hard to imagine that the Nazi saw himself as a moral, quiet, upstanding family man who was fighting the brave fight to bring about a better world. But that’s surely closer to the truth than the carricature I painted. We find it inconceivable that P.H. Anderson might have thought that Jourdan Anderson would have been better-off and happier in P.H.’s home and that he’d have come back voluntarily. And yet, P.H. probably did think that. That’s why he sent the letter.

The sad thing is that in other cases it might have well worked. Because that was probably the most evil aspect of slavery. It wasn’t just the perpetrators that accepted the status-quo, it was the victims. Not all, but it would probably have been quite common to “love one’s master”. That’s the scary thing. Stockholm Syndrome is real and shows itself in every instance of systematic oppression, especially if it persists for many generations.

So the ultimate thing to ponder is just how different a moral world P.H. Anderson lived in. Every villain is the hero if his/her own story. That’s why moral progress (or even moral improvement) is so fucking slow.

*I originally wrote this sentence referring to both people by their last names. You know, to stop myself from calling Jourdan Anderson by his first name, as was the common way to infantilise slaves. Then I read back the sentence: “Anderson wrote asking Anderson to come back to work for him” and remembered that of course slaves were given their master’s surname. The extent of the patronisation was shocking since I did forget. I have therefore opted to use Jourdan Anderson’s full name. I couldn’t find what P.H. stood for so for now the initials stand.

0 Comments