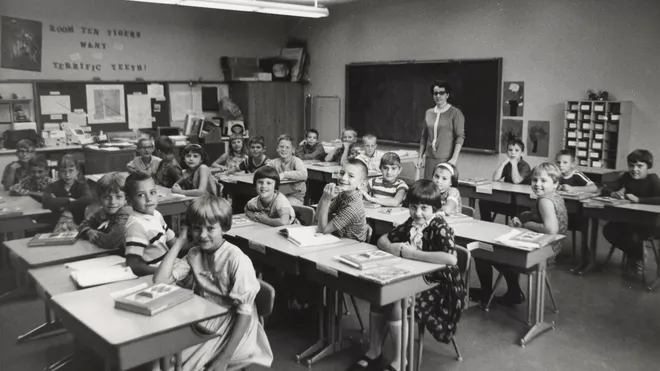

Young members of the Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng Museum, Phnom Penh

It’s a cliche that various horrible events from the 20th century have changed the popular understanding of human behaviour — but it’s true. It particularly hit me in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum looking at photos of the young Khmer Rouge. The public school that the Khmer Rouge turned into their torture quarters has been left as-is. What makes the museum (and perhaps the Khmer Rouge genocide) stand out is the total breakdown of the perpetrator-victim dichotomy. Staring at the countless of faces of young boys and girls who took up implements of torture with gladness are enough to make anyone’s skin crawl. Not because they did this as some Other — because each of us could have so easily been one of them.

The discipline that proves this is experimental psychology, which is full of results that are frankly terrifying. Some examples, just in case they’re not familiar. (The first two are widely criticised for methodology, interpretation and applicability to the wider world but are still important to know about):

- The Milgram experiment: Subjects were “testing” a learning style where a third party gets electric shocks for wrong answers. With escalating pressure from the experimenter, 65% of subjects delivered a [fake] fatal shock despite the “student” pleading to leave.

- The Stanford Prison experiment: A group of students role-played inmates and guards, and the guards instantly became so brutal that the experiment was ended early. This one is very flawed but even with that in mind, the speed at which things escalated is astounding.

- The Good Samaritan experiment: Theology students were sent across campus to preach about the Good Samaritan. On their way they encountered someone pretending to be in serious need of medical help. Despite the strong parallels with the sermon they were about to preach, subjects who were in a hurry did not stop to help.

- The bystander effect: Basically if you are in trouble (eg. being assaulted), the more people are around, the LESS likely it is that you’ll get help.

- The robbers cave experiment: “The experiment, conducted in the bewildered aftermath of World War II, was meant to investigate the causes—and possible remedies—of intergroup conflict. How would they spark an intergroup conflict to investigate? Well, the 22 boys were divided into two groups of 11 campers, and ——and that turned out to be quite sufficient.” There was no need to proceed to stage 2, that was enough for some massive hostilities.

The validity of psych experiments has been in the news lately because they mostly focus on WEIRD uni students. (WEIRD = People from Western Educated Industrialised Rich Democratic countries, a group shown to be psychologically extreme compared to other groups). But even then, there are dozens of scary findings about how WEIRD people, if not all people, behave.

Being aware of some of these might improve people’s behavior. I’ve encountered this anecdotally when reading about the bystander effect just beforehand caused me to help someone being assaulted pretty quickly. I don’t like to think about what I’d have done otherwise.

Learning about these is therefore very worthwhile. And childhood would be the best time to internalise the message. We all think “I wouldn’t do that” but so what? The vast majority of us are wrong.

So how do we do it?

An old fantasy of mine was to have a society where being an unwitting participant in a Milgram-style experiment was a rite of passage. Say at age 12. It would be traumatic as fuck but the memory of having delivered that final shock with your own hands could do a lot of good. Now I’m a tad more aware of all the negatives (and unknowns) so happy for it to remain a thought experiment.

Something milder has been done by Jane Elliott who created a classroom exercise which was a milder version of the robber cave experiment. She divided the classroom based on eye colour and began to privilege people of one eye colour while dehumanising those of the other colour (yep, who needs those pesky ethics?!). The situation was then reversed and finally the students got a debriefing.

One slightly less traumatic way to get a similar message across is through the arts. I got to see a great example of this a few weeks ago in the Australian Theatre for Young People’s play Compass, by Jessica Bellamy. The play explores how a group of school kids who lose their teacher on a camping trip interact with each other, and how they treat an outsider. The play shows the threat of the Other and the use of fear and dehumanisation to quickly change the group dynamics in a horrible way. In other words, it’s our old psych experiments personified and brought to within arm’s reach – the small room setting helped.

The play was targeted to kids and above making it accessible. It was a great way to introduce kids to the ease with which you (yes, YOU) can switch to inhumanity. The play also delves into the tension between our beliefs and the role we find ourselves in during a bad situation, as well as the cognitive dissonance we all apply to excuse ourselves. Which is of course at the root of many of the scary experimental results. It also describes the uncertainty of it all – the kids who come through in the end aren’t those we’d have predicted, which may empower kids with the idea that they can overcome their nasty impulses regardless of their background.

I think that’s a much less horrific initiation than putting kids through the Milgram experiment of even Jane Elliott’s class. It would be very interesting to see someone introduce more of these harsh realities to viewers of school age and below.

Of course this brings to mind another question: do the arts make for better people or is that a very 18th century Enlightenment dead white landowning male idea? Luckily, answering that’s above my paygrade.

0 Comments